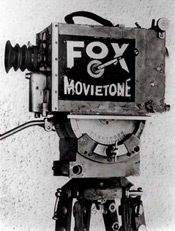

Movietone sound system

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

The Movietone sound system is an optical sound-on-film method of recording sound for motion pictures, ensuring synchronization between sound and picture. It achieves this by recording the sound as a variable-density optical track on the same strip of film that records the pictures. The initial version of this system was capable of a frequency response of 8500 Hz.[1] Although modern sound films use variable-area tracks instead, modern motion picture theaters (excluding those that have transitioned to digital cinema) can play a Movietone film without modification to the projector (though if the projector's sound unit has been fitted with red LED or laser light sources, the reproduction quality from a variable density track will be significantly impaired). Movietone was one of four motion picture sound systems under development in the U.S. during the 1920s. The others were DeForest's Phonofilm, Warner Brothers' Vitaphone, and RCA Photophone. However, Phonofilm was principally an early version of Movietone.

History[edit]

As a student, Theodore Case developed an interest in using modulated light to carry speech. In 1916, he established a laboratory to research the photo-electric properties of materials. He developed the Thalofide cell, a sensitive photocell that was utilized as part of an infrared communication system by the U.S. Navy during, and for some years after, World War I.

In 1922, Case and his assistant, Earl I. Sponable, shifted their focus to "talking pictures." During that year, Case was approached by Lee de Forest, who had been trying since 1919 to develop an optical soundtrack for motion picture film in a system he called Phonofilm. De Forest was not having much success and sought help from Case. From 1922 to 1925, Case and de Forest collaborated in developing the Phonofilm system. Among Case's other inventions, he contributed the Thalofide photocell and the Aeo-light, a light source that could be easily modulated by audio signals and could finally be utilized to expose the soundtrack in the film of sound cameras.

In 1925, however, Case ended his relationship with de Forest due to de Forest's tendency to claim the entire credit for the Phonofilm system for himself even though most of the critical inventions had come from Case. Documents supporting this, including a signed letter by De Forest that states that Phonofilms are only possible because of the inventions of Case Research Lab, are located at the Case Research Lab Museum in Auburn, New York.[2] In 1925, therefore, Case and Sponable continued developing their system, which they now called "Movietone".

Since 1924, Sponable focused on designing single-system cameras that could record both sound and pictures on the same negative. He requested Bell & Howell to modify one of their cameras according to his design, but the results were unsatisfactory. As a result, the Wall machine shop in Syracuse, New York was tasked with rebuilding this camera, and the results were significantly improved.

Subsequently, Wall Camera Corporation produced numerous single-system 35mm cameras, which eventually led to the later development of the three-film Cinerama "widescreen" cameras in the 1950s. Initially, Wall converted some Bell & Howell Design 2709 cameras to single-system, but most were designed and produced by Wall. Single-system cameras were also made by Mitchell Camera Corporation during World War II for the U.S. Army Signal Corps, although these cameras were relatively rare.

The aspect ratio of approximately 1.19:1 was introduced with the development of single-system camera technology. This came about from overlaying an optical soundtrack on top of the 35mm full aperture, which became colloquially referred to as the "Movietone ratio." This ratio was widely used by Hollywood and European studios (apart from those that adopted sound-on-disc) between the late 1920s and May 1932, when the Academy ratio of 1.37:1 was introduced, effectively restoring the original frame shape of the silent era.

In the 1950s, the first 35mm kinescope camera with sound-on-film was introduced by Photo-Sonics. This camera featured a Davis Loop Drive mechanism built within the camera box, which was essential for TV network time-shifting before the use of videotape. The sound galvanometer, made by RCA, was designed to produce good to excellent results when the kinescope film negative was projected, thereby avoiding the need to make a print before the delayed replay. The Davis mechanism was developed by Western Electric.

After parting ways with de Forest, Case made changes to the projector soundhead. It was now positioned below the picture head, with a sound-picture offset of approximately 14+1⁄2 inches (370 mm) (close to the present-day standard), rather than being placed above the picture head as previously done in Phonofilm practice. Case also adopted the 24 frames/sec speed for Movietone, aligning it with the speed already chosen for the Western Electric Vitaphone sound-on-disc system. This established 24 frames/sec as the standard speed for all sound films, whether sound-on-disc or sound-on-film and has remained the standard speed for professional sound films with a few exceptions.[3][4]

At this point, the Movietone system was adopted by the AMPAS as the academy's standard. It and the later RCA Photophone system were interchangeable in most respects. See RCA Photophone for technical details and lists of the industry adopters.

Commercial use by William Fox[edit]

The commercial use of Movietone began when William Fox of the Fox Film Corporation purchased the entire system, including the patents, in July 1926. Despite Fox owning the Case patents, the work of Freeman Harrison Owens, and the American rights to the German Tri-Ergon patents, the Movietone sound film system utilized only the inventions of Case Research Lab.

Also in 1926, William Fox hired Earl I. Sponable (1895–1977) from Case Research Lab and acquired the sound-on-film patents from Case. The first feature film released using the Fox Movietone system was Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927), directed by F. W. Murnau. This film was the first professionally produced feature film with an optical soundtrack. The sound in the film included music and sound effects but only a few unsynchronized spoken words. The system was also used for sound acting sequences in Mother Knows Best (1928).

Within two years after purchasing the system from Case, Fox bought out all of Case's interests in the Fox-Case company. All of Fox's sound feature films were made using the Movietone system until 1931 when it was superseded by a Western Electric recording system that utilized the light valve invented by Edward C. Wente in 1923. Despite this change, Fox continued to use the Movietone system for the Movietone News until 1939 due to the convenience of transporting the single-system's sound film equipment.

Later development[edit]

The Case Research Lab's sound system substantially impacted industry standards. For instance, it positioned the optical sound 20 frames ahead of the accompanying image.[3][4][5] The SMPTE standard for 35 mm sound film is +21 frames for optical, but a 46-foot theatre reduces this to +20 frames.[6][7] This adjustment was made partly to ensure that the film runs smoothly past the sound head, but also to prevent Phonofilms from being played in theaters – as the Phonofilm system was incompatible with Case Research Lab specifications – and to ease the modification of projectors already widely in use.

Sponable worked at the Fox Film Corporation (later 20th Century Fox) Movietone studios on 54th Street and 10th Avenue in New York City until he retired in the 1960s, eventually winning an Academy Award for his technical work on the development of CinemaScope. Sponable made numerous contributions to film technology, including the invention of the perforated motion-picture screen. This innovation allowed speakers to be placed behind the screen to enhance the illusion of sound emanating directly from the film action. During his time at Fox, Sponable also served as an officer of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers. He published a concise history of sound film in the April 1947 issue of The SMPE Journal (The SMPTE Journal after 1950).[3]

The history of Case Research Lab was long unheralded. After Theodore Case passed away in 1944, he left his home and laboratory as a donation to be preserved as a museum showcasing the inventions of Case Research Lab. However, the museum's first director, who oversaw it for 50 years, decided to put the laboratory's contents into storage and converted the building into an art studio. The Case Research Lab sound studio was located on the second floor of the estate's carriage house, which had been rented to a local model train club until the early 1990s.

After sustaining severe injuries in a car accident in July 1929, Fox lost his company in 1930 when his loans were called in. In 1936, he also lost a lawsuit in the U.S. Supreme Court against the film industry, which he believed had violated his Tri-Ergon patents. Sponable had done very little to establish the historical record of Case Research Lab inventions, apart from his April 1947 article in The Journal of the SMPE.

It was also in 1947 that the Davis Loop Drive was introduced to Western Electric licensees, including Twentieth Century-Fox (WECo RA-1231; still made by a successor company). [citation needed]

The Case Research Lab, the adjoining carriage house, and Case's home have been restored. Research using the lab receipts, notebooks, correspondence, and much of the laboratory's original equipment is ongoing. This includes the first recording device created to test the AEO light. The collections include letters from Thomas Edison, a copy of the Tri-Ergon patents, and an internal document from Fox Films written in the 1930s. This latter document states that once it became public knowledge that Sponable perfected the variable-area sound-on-film system at the Fox Studios, that system became the standard and superseded the inventions of Case Research Lab.

Several films owned by Case Research Lab and Museum were restored by George Eastman House in Rochester, New York and are in their collections. The Case Research Lab and Museum has additional sound-film footage of Theodore Case. Recently discovered copies of the same films at the Eastman House are in a much better state of preservation. Movietone News films are in the collections of 20th-Century Fox and the University of South Carolina at Columbia. This includes the only known footage of Earl I. Sponable talking. Sponable can also be seen in footage of the premiere of the film The Robe.

Phonofilms that were produced using Case Research Lab inventions are in the collections of the Library of Congress and the British Film Institute.

The variable density (VD) recording systems developed by Movietone gradually lost market share to variable area (VA) systems developed by Photophone after the 1940s. This shift accelerated as VA-related patents expired. Both methods can, in theory, achieve similar standards of recording, duplication, and reproduction. However, quality control in the lab became much more critical in duplicating VD tracks than VA tracks. Minor inaccuracies in printer light settings, sensitometry, and densitometry control had a greater impact on the signal-to-noise ratio of a VD track compared to a VA track. For this reason, archives, have opted to remaster original VD tracks to VA negatives for preservation and the creation of new prints.

See also[edit]

- Phonofilm

- Vitaphone

- RCA Photophone

- Photokinema

- Movietone News

- Joseph Tykociński-Tykociner

- Eric Tigerstedt

- Sound film

- Movie projector

- Sound-on-disc

- List of film formats

- List of early sound feature films (1926–1929)

References[edit]

- ^ "Motion Picture Sound - part 1". Audio Engineering Society. 2017-07-01. Archived from the original on 2017-07-01. Retrieved 2021-01-02.

- ^ "Cayuga Museum of History and Art". Retrieved 2021-01-02.

- ^ a b c Earl I. Sponable, "Historical Development of Sound Films," The Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers (April 1947), Vol. 48, No. 4

- ^ a b Edward Kellogg, "History of Sound Motion in Pictures," The Journal of the Society of Motion Picture Engineers (June 1955), Vol. 64, p. 295

- ^ Leslie J. Wheeler, Principles of Cinematography (4th ed.), Fountain Press (1969), p. 373

- ^ Kodak Film Notes Issue # H-50-03: Projection practices and techniques – see Manuals at http://www.film-tech.com/

- ^ Ira Konigsberg, The Complete Film Dictionary (2nd ed.), Bloomsbury (1997) – see Projector article.